5.1 The Date (of the prophet’s ministry and work)

5.1 The Date (of the prophet’s ministry and work)

Second Kings 14:25 sets the general date of Jonah’s ministry during the reign of Jeroboam II of Israel (793-753 B.C.). Although the book’s historical setting is without question, the date of composition is uncertain because (unlike other prophetic books) Jonah does not record its author. Dillard and Longman note “the book contains no indication of author or date of composition.”[54] Wood takes the position that “Jonah no doubt wrote his book after he returned from Nineveh to Israel, when he could look back and assess more objectively the events that had transpired.”[55] Wood also examines Assyrian history for clues pointing to a more exact date. His analysis favors a date about 760 because several factors were present that could have influenced the Ninevites’ positive response to Jonah’s message of coming judgment. Wood’s conclusion is plausible, but it is safer to be less specific and date the book according to the biblical record sometime during Jeroboam II’s administration.

5.2 Background History (historical setting of the prophet)

A message of doom directed toward Assyria, Israel’s feared and hated neighbor, would have been wildly popular to the ear of the Jew. The Lord was finally ready to destroy their Goliath-sized enemy and deliver David-sized Israel from oppression. God’s timing seemed to be perfect as

Assyria was preoccupied with the mountain tribes of Urartu and did not continue her westward campaigns until Tiglath-pileser III (745 B.C.) came to power. Israel rejoiced in the Assyrian preoccupation. She aggressively pursued a policy of defense by strengthening the fortified cities, building up the army, and employing international diplomacy.[56]

Jonah was called by the Lord to preach to the inhabitants of the Assyrian city of Nineveh, which infuriated the prophet. He was well aware of God’s gracious nature, and did not want to warn Israel’s enemies for fear that they might repent and God would thus relent. Jonah desired that Nineveh, widely known for their cruelty,[57] be punished more than he desired the salvation of the large Gentile city.

At home in Israel, the nation was experiencing a period of great material prosperity and spiritual deterioration. Jonah ministered in the eighth century within the same environment as Hosea and Amos.

5.3 Work and Person (character and ministry of the prophet)

The references outside the book of Jonah provide most of his known biographical information. Despite the argument that the story of Jonah is an allegory, Jonah was a historical person who served as a prophet to Israel during the reign of Jeroboam II. His father was Amittai (Jonah 1:1), he made his home in Gath-Hepher (a town northeast of Nazareth in the Galilean region), and prophesied that Jeroboam II would expand the territory of Israel “from the entrance of Hamath to the sea of the God of Israel” (II Kgs. 14:25). Beyond such details, the canonical book that bears his name allows us a window to his soul.

Bullock summarizes the human side of Jonah portrayed in the story:

The character lines in the book are well drawn, and we feel that we know Jonah quite well when the story concludes. He had a mind of his own. Even when he knew he had lost the war, he still waged his personal battle (4:1-11). The book is short on oracular material (only 3:4b), and the psalm of chapter 2, although not an oracle, reveals one side of the prophet’s disposition, balanced precariously against another side drawn out in chapter 4…It was a very human reaction that Jonah should be thankful for his own deliverance but resentful about Nineveh’s.[58]

Wood garners other glimpses into the complicated personality of Jonah.[59] He was “interested in the destruction of Ninevites, not their salvation;” he “must have been a true man of God to be called to the important mission to Nineveh;” he demonstrated a lacking in “complete dedication of life” to the Lord; his thinking was “not free from a narrowmindedness that was characteristic of Jews of the day” regarding God’s blessing on the Gentiles; but “one can hardly characterize Jonah as lacking in courage” as he faced the angry waves from the ship; and he “must also have been a gifted speaker” to be heard above the rest of the foreign messengers that no doubt spoke in Nineveh.

Jonah is a fascinating character in part because he is flawed. God’s people struggling against sin and selfishness no doubt can relate to Jonah. Dillard and Longman point out that “Jonah is not a flat, but a complex character. That is, in his spiritual ups and downs he acts like a real person. This roundness of character is one of the reasons that Jonah is such a fascinating and rich book.”[60]

5.4 The Book (abbreviated outline[61] and brief summary)

I. Jonah’s Disobedience and God’s Reaction (1:1-2:10)

A. Jonah Flees From God’s Call (1:1-3)

B. God Sends a Great Storm (1:4-15)

C. Jonah’s Flight Is Ended (1:16-17)

D. Jonah’s Prayer and God’s Response (2:1-10)

1. Jonah Prays With Thanksgiving (2:1-9)

2. God Answers Jonah’s Prayer (2:10)

II. Jonah’s Obedience and God’s Reaction (3:1-4:11)

A. Jonah Obeys God’s Call (3:1-4)

B. Ninevites Repent and God Responds With Compassion (3:5-10)

C. Jonah’s Prayer and God’s Response (4:1-11)

1. Jonah Prays With Anger and God Answers (4:1-4)

2. Jonah Receives Further Explanation From God (4:5-11)

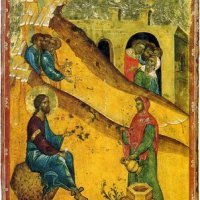

The story of Jonah is easy to summarize, however the intended message is notoriously difficult to identify. Jonah describes himself in the first chapter as a Hebrew who fears “the LORD, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land” (1:9). He serves as a prophet for God, but when God calls him to a new assignment of preaching judgment to the hated Ninevites, Jonah balks and instead decides to disobey and sail to Tarshish which was effectively on the other side of the world (1:3). The Lord follows in pursuit of his wayward servant and sends a harrowing tempest that nearly destroys the ship (1:4). After Jonah confesses his disobedience, the mariners, with Jonah’s approval, toss Jonah overboard to appease the deity who brought the troublesome storm upon them. Jonah sinks to the bottom of the sea, repents, and thus God delivers him to shore by way of the belly of a great fish, which vomits him onto dry land (2:10). The Lord then commissioned Jonah again to go preach in Nineveh and this time the servant obeys the command. After delivering the message, Jonah’s worst fears are realized—the Ninevites repent and God gives them grace. The book concludes with Jonah complaining to God for being gracious to the enemy nation and for his own lack of creature comforts, and God responding with chiding words regarding Jonah’s poor attitude towards God’s grace and providence (4:8-11).

What are we to make of such a unique prophetic book? Robertson writes that “Jonah distinguishes himself among the prophetic books from several perspectives.”[62] Jonah is almost completely a narrative, except for the single sentence oracle in Jonah 3:4. Jonah is also the only writing prophet sent to a foreign nation. In addition, there are questions about the literary genre of the book—is it didactic fiction (parable) or didactic history? Despite the belief that this “question is irrelevant to the interpretation of the book”[63] and that “the question of the intention of historicity is totally without effect on the interpretation of the book’s theological message or even the exegesis of individual passages,”[64] we must remember that Jesus himself used the example of Jonah’s three days and nights in the belly of the fish as a sign of his own historical death, burial, and resurrection. This single argument should be sufficient to establish the book’s historicity.

Much has been written of the book’s theological theme. Many read Jonah as a lesson on God’s compassion for the Gentiles and a stern rebuke to Israel for presuming that its special status gave it a monopoly on the grace of God. This understanding focuses on God as “the God of Israel, the God of Nineveh, the God of the entire creation.”[65] Others see the theme of worship and thanksgiving in chapter 2. Still others argue that the sovereignty of God and how his rule operates in the world is primary.[66] McConville offers sound advice on finding the point of Jonah.

Should we expect to find that a story like Jonah has only one point? If Jonah is meant to teach that God may repent of his intention to judge, what is the point of it being a story about Nineveh? Is that just incidental?…is not the idea of Assyrians turning to Yahweh the God of Israel bound to make an impact on Israelite or Jewish hearers? Good stories rarely have just one point.[67]

Endnotes

54. Dillard and Longman, Introduction to the Old Testament, p. 391.

55. Wood, Prophets of Israel, p. 290.

56. Van Gemeren, Interpreting the Prophetic Word, p. 146.

57. Wood, Prophets of Israel, p. 292.

58. C. Hassell Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament Prophetic Books (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1986), p.44.

59. All quotations in this paragraph are from Wood, Prophets of Israel, pp. 292-93.

60. Dillard and Longman, Introduction to the Old Testament, p. 394.

61. “Jonah,” in Spirit of the Reformation Study Bible, p. 1461.

62. Robertson, Christ of the Prophets, p. 250.

63. Dillard and Longman, Introduction to the Old Testament, p. 393.

64. Ibid.

65. Ibid., p. 395.

66. J. Gordon McConville, Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Prophets (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2002), p. 189.

67. Ibid., p. 191.